Building a Culture of Health

The role of actuaries in affecting the health of their communities

February 2018 Web ExclusiveThe Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) developed a “Culture of Health Action Framework” to “set a national agenda to improve health, well-being and equity.”1 The RWJF website states: “Our health is greatly influenced by complex factors such as where we live, and the strength of our families and communities. But despite knowing this, positive change is not occurring at a promising pace. To accelerate progress, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has proposed a vision for a national Culture of Health where everyone has the opportunity to live a healthier life.”2

Such a vision can only be realized through thoughtful action that considers both outcomes and costs. Actuaries are knowledgeable about the impact of interventions on outcomes and costs, as well as the role insurance can play in effectuating change in their communities. For example, actuaries can quantify the present value of program and services costs, and actuaries are grounded in concepts that can be used as summary measures of health, such as life expectancy.

Life expectancy differs across U.S. counties,3 with studies showing the association between income and life expectancy.4 Researchers also have written about the benefits of health on happiness.5,6 While there is general agreement that the growth in health care spending is unaffordable, there is a wide variety of opinions—among actuaries, researchers and the public at large—as to what are the next steps to improve health outcomes while reducing health care spending.

The Society of Actuaries (SOA) Health Section’s Public Health Strategic Initiative7 strives to motivate actuaries to engage in public health initiatives. This article summarizes the RWJF Culture of Health Action Framework and a related article surveying Americans’ attitudes about personal health and the role of government in health. Finally, I illustrate the intersection of these topics with potential contributions by actuaries.

RWJF CULTURE OF HEALTH ACTION FRAMEWORK

The RWJF “Culture of Health Framework” promotes greater health equity across the United States. The RWJF website states: “Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be healthier. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments and health care.”8 The process of removing substantial differences entails identifying whether these obstacles exist and measuring the extent of any obstacles with the goal of initiating change through public policy and practices.

The link to successful achievement of health equity, RWJF believes, is through efforts at the community level. Health equity has been linked to well-being, economic vitality and national security.9 If social inequities, such as income, wealth or education, were addressed, then there could be a greater chance of success of health equity.10

HEALTH AFFAIRS CULTURE OF HEALTH ISSUE

The November 2016 issue of the journal Health Affairs was devoted to articles related to the “Culture of Health.” One article featured an interview with Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, then-president and CEO of RWFJ, in which she discussed her vision with this new initiative.11 The conclusion of this interview was that although other initiatives such as increasing insurance or reducing smoking rates may have been successful, societal goals of improving population health were not met. New evaluation tools are needed to determine whether a culture of health has or has not been achieved.12

Another article in this November 2016 issue titled “Promoting Health Equity And Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ”13 connects how the Health Section’s Strategic Initiative goal to engage actuaries in public health might best be communicated to actuaries. My goal with this article is to meld the ideas and conclusions presented in that article with comparisons to practicing as actuaries and their potential role in promoting or influencing a culture of health.

PROMOTING HEALTH EQUITY AND POPULATION HEALTH

“Promoting Health Equity and Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ” measured the receptivity of Americans to RWJF’s vision for the Culture of Action Framework with regard to a shared value of increased civic engagement of health and well-being. The goal was to create some market segmentation of views of personal health and the role of government in creating or maintaining population health. To achieve this segmentation, a survey was created using a complex survey design so that results were representative of U.S. adults aged 18 and older. Adjustments were made for not completing or not responding to the survey.

The survey posed 46 questions, some with multiple parts. Questions ranged from asking respondents about their happiness, health and education, to their views on topics including taxes, immigration, climate change and politics. Respondents were asked to take the view of policymakers and answered questions about how they assessed health priorities relative to other initiatives. Respondents also were asked to define “health” and whether or not they made “health” a priority for themselves.

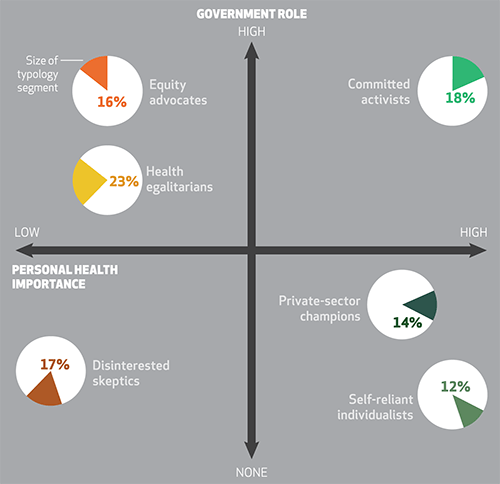

Figure 1 highlights the results of this study. Six clusters were found to represent the values of Americans regarding their personal health and the role of government in achieving population health. A two-dimensional plane illustrates the divergence of views of the American population. Starting in the upper-left quadrant and moving clockwise, the first quadrant represents those who value the role of government in achieving population health but not their personal health. The second quadrant represents those who value both the role of government in achieving population health and their personal health. The third quadrant represents those who do not value the role of government in achieving population health but do value their personal health. The fourth quadrant represents those who value neither the role of the government in achieving population health nor their personal health. While not equally distributed, the clusters represent sizable percentages of Americans with vastly different views.

Figure 1: Typology of Americans’ Health Values

Source: American Health Values Survey, 2015–2016. Notes: The percentages show the relative size of each segment. Segments in the upper quadrants favor a stronger government role in population health relative to segments in the lower quadrants. Segments in the right-side quadrants place higher importance on personal health relative to segments in the left-side quadrants. Placement along the axes approximates the strength of beliefs.

Copyrighted and published by Project HOPE/Health Affairs as Larry Bye, Alyssa Ghirardelli, Angela Fontes, “Promoting Health Equity and Population Health: How American’s Views Differ,” Health Aff (Millwood): 2017; 35(11). The published article is archived and available online at www.healthaffairs.org.

The article presents broad summaries of the clusters. Some of the differences in responses between clusters are nuanced; others are quite dramatic. An appendix to the article summarizes the demographic, political and health characteristics of the six clusters.

The authors of the study felt that one of the important discoveries was that those who do not believe in the role of government in promoting health could be receptive to community initiatives to improve health, as long as there was a strong role of private-sector engagement in these activities. The primary conclusion of the article is that communication tailored specifically to each cluster could be effective in motivating individuals by recognizing the differences among cluster perspectives.

RELEVANCE TO ACTUARIES

Health actuaries are involved in making decisions or facilitating the decision-making process to value interventions such as wellness programs or the trade-off of choices among drugs for use in care. Obviously, all actuaries are not of the same mindset nor do they have the same underlying belief systems. The distribution of the population of actuaries with regard to the six clusters in the “Promoting Health Equity and Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ” article is unknown, but we can assume that the clusters are all represented in some proportion.

As such, our process to decision-making regarding the value of public health initiatives may differ depending upon in which cluster we reside. Having access to information from alternate perspectives or other disciplines may be useful to introduce ideas and concepts, influence perspectives, model the value of interventions and guide decision-making. The perspectives of those in all clusters are important for designing optimal approaches that can be seen by all as having positive potential.

For example, suppose a wellness program is being considered for an employer. A return on investment (ROI) was calculated, and because of the employer’s relatively short-term planning horizon, it was determined that the initiative would not be effective. However, consistent with the conclusions “Promoting Health Equity And Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ,” all clusters may be amenable to investment in community health, as long as there is private-sector involvement. That is, community-based wellness programs may have the longer-term horizon needed to generate a satisfactory ROI. Moreover, it could be that, when provided with research that improving education improves the health of the community and would lower health care costs in the future, all clusters would be amenable to investment in education in their communities.14,15,16,17,18

The role of actuaries, regardless of their area of specialization, is relevant to improving the health and welfare of communities. We want to live in communities where we feel safe and happy, and have a good quality of life. Whether we are “self-reliant,” “disinterested skeptics” or from one of the other four clusters, we have a vested interest in the long-term health of the communities where we reside. In our roles as consumers and as actuaries, we can pursue change that stays true to our fundamental beliefs. We can motivate others to work toward the greater good or other fundamental goals by speaking to them in their language and using approaches that are fundamentally sound to achieve general buy-in.

To isolate initiatives relating to health care from other initiatives like safe water, improving education or job creation is short-sighted. Aggregating the portfolio of initiatives to leverage outcomes is in the best interests of all, regardless of perspective. Safer and healthier communities occupied by those who are critical-thinkers and have jobs results in a decrease of health care costs, and a decrease in the numbers and costs of those on government assistance, and raises the population health of communities. The difficulty is balancing short-term needs and costs with long-term benefits.

Actuaries are uniquely positioned to help improve the health of their communities by helping in the design of appropriate, cost-effective strategies to achieve the established goals. We have the technical skills and knowledge to understand complicated processes to suggest changes that consider both the costs and the outcomes. Now is our time to make a greater societal impact.

References:

- 1. “Building a Culture of Health.” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. ↩

- 2. Supra note 1. ↩

- 3. Dwyer-Lindgren, Laura, Amelia Bertozzi-Villa, Rebecca W. Stubbs, Chloe Morozoff, Johan P. Mackenbach, Frank J. van Lenthe, Ali H. Mokdad , and Christopher J. Murray. 2017. “Inequalities in Life Expectancy Among U.S. Counties, 1980 to 2014: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers.” JAMA Internal Medicine 177 (7):1003–1011. ↩

- 4. Chetty, Raj, Michael Stepner, Sarah Abraham, Shelby Lin, Benjamin Scuderi, Nicholas Turner, Augustin Bergeron, and David Cutler. 2016. “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014.” JAMA 315 (16): 1750–1766. ↩

- 5. Graham, Carol 2008. “Happiness and Health: Lessons—and Questions—for Public Policy.” Health Affairs 27 (1): 72–87. ↩

- 6. Zajacova, A., and J.B. Dowd. 2014. “Happiness and Health Among U.S. Working Adults: Is the Association Explained by Socio-economic Status?” Public Health 128 (9): 849–851. ↩

- 7. Teppema, Sara. 2017. “Public Health: The New Frontier A Health Section Strategic Initiative.” Health Watch 83: 18–19. ↩

- 8. Braveman, P., E. Arkin, T. Orleans, D. Proctor, and A. Plough. 2017. “What Is Health Equity?” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. May 1. ↩

- 9. “Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity.” 2017. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. January 11. ↩

- 10. Supra note 9. ↩

- 11. Weil, Alan R. 2016. “Building a Culture of Health.” Health Affairs 35 (11): 1953–1958. ↩

- 12. Weil, Alan R. 2016. “Defining and Measuring a Culture of Health.” Health Affairs 35 (11): 1947. ↩

- 13. Bye, Larry, Alyssa Ghirardelli, and Angela Fontes. 2016. “Promoting Health Equity and Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ.” Health Affairs 35 (11): 1982–1990. ↩

- 14. Behrman, J. R., and Nevzer G. Stacey. 2014. The Social Benefits of Education. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ↩

- 15. Alsan, Marcella, Anlu Xing, Paul Wise, Gary L. Darmstadt, and Eran Bendavid. 2017. “Childhood Illness and the Gender Gap in Adolescent Education in Low- and Middle-income Countries.” Pediatrics. ↩

- 16. Klein, Jonathan D., and Errol R. Alden. 2017. “Children, Gender, Education, and Health.” Pediatrics 140 (1). ↩

- 17. McGinnis, J. Michael 2016. “Income, Life Expectancy, and Community Health: Underscoring the Opportunity.” JAMA 315 (16): 1709–1710. ↩

- 18. Woolf, Steven H., and Jason Q. Purnell. 2016. “The Good Life: Working Together to Promote Opportunity and Improve Population Health and Well-being.” JAMA 315 (16): 1706–1708. ↩